This upcoming February 2019, Vienna will receive the workshop " Algorithmic Accessories v4.0 " which is organized by DesignMorphine and taught by two of their most experienced tutors: Eva Blšáková and Lidia Ratoi.

We've talked about DesignMorphine in the past, but for those new to them, they're mainly a creative hub for design through workshops, lectures, projects and explorations in the fields of architecture, design and arts.

In this occasion we took this opportunity to talk directly with both of the tutors in charge of this workshop to learn more about their background, thoughts on parametric design, wearables, mass customization and product design in general.

1. What are your backgrounds?

Eva: I have been involved in the art & design industry for almost a decade. As an architectural designer I received a Master Degree in Architecture at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, where I studied under Prof. Zaha Hadid.

Because of my big passion for innovation, digital fabrication and rapid prototyping I started Fab Academy in IAAC in Barcelona, where I also assisted several projects in Fab Textiles Lab. My Bachelor from Faculty of Multimedia Communication at UTB in Zlin included also marketing and design and I got experience not just in the multimedia and arts, but also in the field of public relations and organization of exhibitions. During my studies, I worked in Bollinger+Grohmann Ingenieure and after receiving my degree I gained professional experience in diverse architectural offices such as Coop Himmelb(l)au, DMAA, GR Design. I also collaborated with Noumena and Reshape.

I am a member of DesignMorphine and last year, together with DM, we organized Algorithmic Accessories V3.0 Workshop in Vienna and we are so excited to continue this year too! In addition to this I am also participating in media activities on a regular basis, what includes publishing on various online and printed platforms. Recently I took over the SYNArchitecture platform and together with my co-founders we are planning to enhance our activities in various fields! So stay tuned!

Lidia: I started (and finished) my architectural studies in Bucharest, Romania, majoring in Interior Architecture. Having discovered (luckily quite early) computational design, after my master thesis I decided to go to IAAC, Barcelona, where I followed the Open Thesis Fabrication program, focusing on large-scale robotic printing using un-fired clay as material.

I then worked briefly for Noumena, Barcelona (by coincidence, Eva and I are doing the Algorithmic Accessories workshop together, and discovered we both went to the same school and worked for the same office but never met). After that I returned to Romania for a while, where I worked for i{n}stance, a bold design studio working with computational design and jewelry-making. I then moved to Copenhagen, where I first worked at SLA / SA, and then at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine arts, as a researcher and teaching assistant.

I’m also an active writer - right now I write for Clot Magazine, and before that I worked for Arch2O magazine, which is how I met Pavlina Vardoulaki, one of the founders of DesignMorphine. After attending one of their workshops (Dynamic Mutations), I became part of the team and in 2017 I tutored the Arte Robotica workshop in Paris, together with my former professor from IAAC, Kunal Chadha, and Amaury Thomas.

DesignMorphine sparked my interest, when I first started interviewing them, due to a large number of reasons: the very ballsy designs, the incredible team of tutors of assistants (much of whom where already famous in the computational design field, 4 years ago when I first wrote about the team), the unique aesthetic approach and the openness to make workshops affordable for students and young professionals.

2. How did you get interested in Parametric/Product Design?

Eva: During my studies at die Angewandte under the influence of the one and only Zaha Hadid… no words needed.

Lidia: The first time I saw something parametric was in my first year of architecture studies - some older students in my school held a workshop and they 3D printed Christmas ornaments. Then, the same year, Matias del Campo, one of the pillars of computational design, came to Romania and gave a presentation which completely changed my view on architecture and design.

Think of The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon. It is a psychological process in which, once you become aware of an element, you start seeing it more often, just because your brain associates it with something familiar. A similar thing happened with me and computational design. First, I joined the rebellious and young team of Atelierul de Proiectare magazine, and through them I went to a Grasshopper workshop focusing on digital fabrication applied to fashion, organized by Parametrica and tutored by the amazing Arian Hakimi Nejad. Arian worked for Zaha Hadid, the founder of parametricism, so my interest in this field sky-rocketed after the workshop, resulting in me and my sister making a collection of laser cut and 3d printed garments and shoes, which were exhibited at FAB10 Barcelona.

That offered a lot of press coverage and allowed me to get known in Bucharest for working with these tools, which at that moment weren’t as popular as now - this was very fortunate, and I got to work in various fields where people were interested in applying computational design - fashion, set design, jewelry and product, interior architecture and even graphics.

3. What is the main idea behind the Algorithmic Accessories workshop?

Eva: In general, events like workshops are great opportunity to get in touch with other like-minded people following similar direction and to exchange information in such a dynamic environment is very intense, especially the Algorithmic Accessories Workshops are extremely standing out. The topic of creating a jewelry piece gives freedom of playing with micro-macro scale, to develop certain design thinking and those methods can be later on applied in various situations too. Previous AA events gathered international students and professionals from a various background with different skill sets, guiding them all through the computational design and fabrication processes and having so much fun aside.

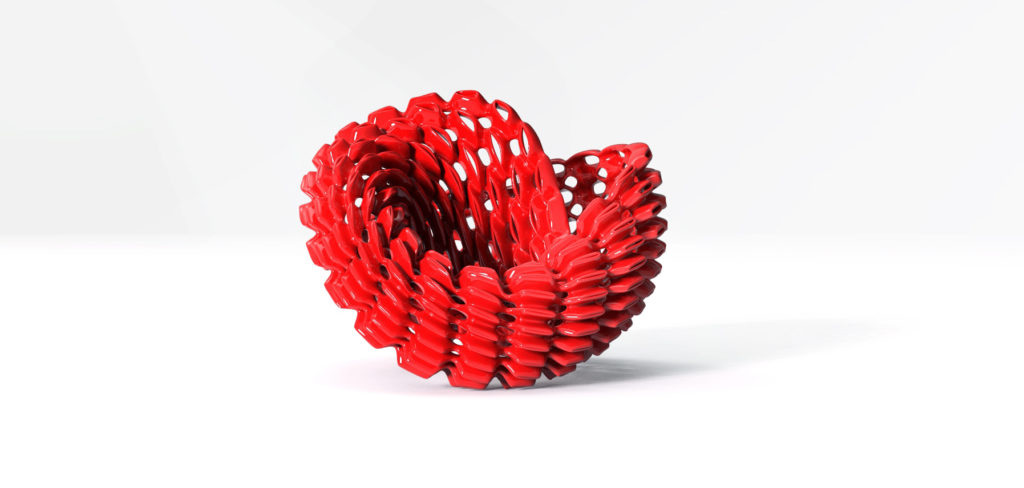

During the workshop, students will create modeling and fabrication strategies for a ring. The challenge will be to design something that is printable, that takes into consideration the logic of the machine and that, of course, is aesthetically relevant in the current design paradigm. More info you can find on the DesignMorphine website, so do not hesitate, apply and join us!

Lidia: While the workshop focuses on jewelry design, this is something that can be extremely useful for architects and designers from other fields - due to the fact that jewelry works with such a small scale, it can be the fastest applied field in which to learn about digital fabrication and computational design. I think that by understanding how to make jewelry you get all the information you need in order to follow the path of digital fabrication: material knowledge, machine knowledge and implementing ergonomic factors. You can then apply this to larger-scale designs, or start experimenting more with jewelry, once you understand the basis of additive manufacturing.

4. What can attendees expect from this course?

Eva: Participants will get an introduction to Grasshopper and algorithmic geometry, they will explore Plug-ins such as Lunchbox, MeshTools, Weaverbird, Mesh+ and Pufferfish developed by the director of DesignMorphine Michael Pryor. No need of previous experience with Grasshopper, the aim is to guide them to understand the algorithm-based methodology and the GH definition in according to get the desired design. Following by the basics of Keyshot rendering to create image material and then getting to creating a physical model by using the fabrication method of 3D printing. The participants will also explore the basics of creating wearable accessories.

Lidia: They can go from having no previous knowledge of computational design software and digital fabrication tools to being able to design and 3D print their own ideas.

What I also love about these workshops is that people work together in an intense-schedule, and they meet others who have the same interests but may be from different background or places. I noticed that at every workshop work-relations are formed, and you get to be in contact with people you might not normally meet.

5. Why are wearables so interesting right now and how will they influence the future of how humans interact with technology?

Eva: Nowadays, the market of wearables is experiencing tremendous increase by devices like smartwatches, activity trackers, navigation tools, smart glasses, etc. The user can easily track his activities and visualizing of those data can be a great tool for motivation to performance improvement.

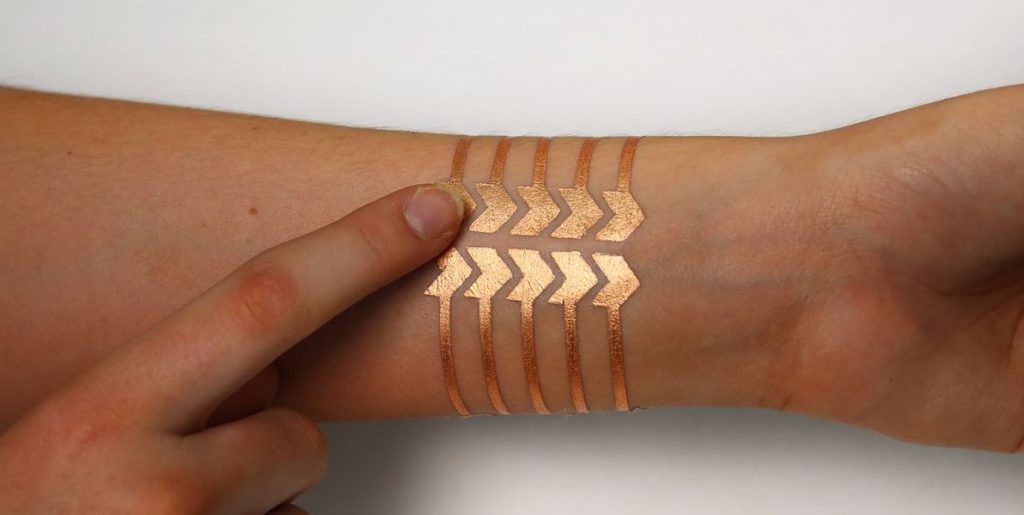

The medical industry is creating wearables that can be embedded underneath the skin. Have you heard about smart tattoos? Currently, they are under the development, it is kind of high-tech temporary tattoos that can transfer information to smartphones. Disney is using MagicBand wearables in its parks to provide visitors access to rides, their hotel rooms, etc.

In my opinion, smart jewelry is the answer for the activity tracking of a fitness band without the inconvenient silicon strap, or without the robust design and awkward screen when compared to a smartwatch. We often see criticisms of their unfashionable aesthetics, so following the jewelry-like wearable devices can emphasize that the consumer could freely modify its appearance and the final piece can be customized.

Because wearables are so new, it's difficult to tell what effects they will have. Fitness trackers create health care trackers and these could be used to monitor things like blood pressure, vital signs, or blood sugar levels for diabetics, also seem to go in the direction of authentication. The same time correct-incorrect measurements of body activities, abuse of data collected while using network or Bluetooth to transmit data means cybercriminals can get their hands on it pretty easily.

There's a lot of potential for wearable technology at the moment. It'll be fascinating to see where everything go from here and how they continue to impact us both individually and as a society.

Lidia: I think it is about time wearables also get included in the high-tech equation. We live in futuristic homes using futuristic machines and software but we still dress and accessorize with things that could have been built 50 years ago. This is a pity, since we have the knowledge and the apparatus to do much more. I personally consider that the more you surround yourself with something the better grasp you have on it - if technology becomes a banal part of your life, you naturally end up mastering and augmenting it.

The great thing with wearables is the small scale - it is a lot more difficult to experiment with architecture or urbanism, whereas in the fashion equation there is a lot more room for trial-and-error experiments.

6. How has Grasshopper changed the way products are developed/designed?

Eva: As we currently experience the age of fast innovation and the same time the acceleration of information is shaping the way we work and interact too, tools we use become more powerful and sophisticated. Therefore we need to evolve and develop our working methods in order to stay competitive. Design process required a lot of tweaking and customization of our tools too according to work the way we need.

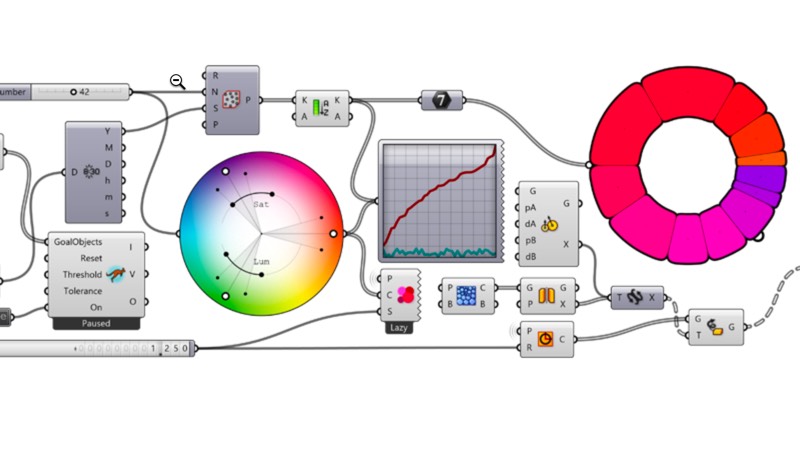

The reality is that not everyone has the time to learn how to code, fortunately, there are new tools that deliver the power of programming without the traditional text-based programming, hence visual programming and most computational design environments rely on it. Visual programming allows you to assemble programs graphically rather than writing code. And Grasshopper (an algorithmic modeling tool for 3D software Rhino) gives you the power of visual programming. You are basically encoding the design, so the result is a graphic representation of the steps required to achieve the end design.

Each step in the design becomes a series of instructions that can be evaluated and improved, each step requires specific parameters. Incorporating visual programming tool as Grasshopper gives us the ability and freedom to explore more design options, think algorithmically and develop your design concept in a more strategic way, at the same time you can access your data faster, it gives you the power to automate repetitive tasks and to test the performance of your design.

Lidia: First of all, it aided the idea of mass customization. With the same script, you can create countless version of the same idea, without having to re-model every time.

What I also like about Grasshopper is that it is very logic based - it doesn’t really have anything to do with how good of a modeller you are, but how well you understand what you want to do. If the process is clear in your mind and you know what to ask for, the process is also clear in Grasshopper. This took out the gap between having ideas and learning a software - Grasshopper is NOT something you learn by heart, just by remembering commands. It is something that you have to understand, you have to create a process, so once you re-compute your brain to think in an algorithm-based manner, the possibilities are endless.

7. What are common misconceptions behind 3D printing, CNC machining and laser cutting?

Eva: Digital fabrication is becoming a part of all branches of design, from architecture to furniture or fashion. Some require large machines, and some can be done with small-scale machines. It always starts with the scale consideration of output object and different objects require different fabrication strategies. I think the main confusion is related to the scale.

I would say 3D printing is an over-hyped technology. It has been around since the 80s, now smaller desktop machines became available and affordable, which will allow all of us to manufacture our own objects. The truth is that the desktop 3D printers are not like industrial ones! People think that they can print everything and that they do not need any other manufacturing techniques. It is not true. In the context of manufacturing, only parts of a suitable level of complexity are economically viable for 3D printing.

Just because you can 3D print, doesn't mean that you should! Always consider the complexity of the printed object and decide if using different manufacturing method e.g. laser cutting or CNC machining would be more efficient and provide a better quality of final output.

Probably the biggest of all 3D printing myth is that every 3D printer will manufacture the same 3D model the same way. Not true at all. The most important factors affecting the quality of 3D prints are extruders, the diameter of their nozzles, printing temperature and speed, build platforms and if they are heated and casing of the machine. Sure, everybody can buy a 3D printer nowadays but not everyone should. Mostly because not everyone would make use of it. Manipulating a 3D printer requires a certain professional knowledge and objects manufactured this way most aren't recognized as end products.

Talking about laser cutting as one of the most efficient methods to cut through a wide variety of materials for manufacturing, lasers can be used on metals, plastics, composites, wood, and more.

People think lasers are hard to operate, but the opposite is the reality. The laser is programmable, with very easy to understand programming capabilities. It can cut patterns through CAD files or vector drawings. You can even change the depth of the cut by adjusting the power and speed parameters of the laser. Modern laser cutters can even self-adjust parameters to different materials and thicknesses.

Lidia: First of all, they are way beyond the experimental phase on which they are perceived commonly. These are established processes which are already perfected, and the only thing we need is to accept them.

Also, I think designers should embrace the aesthetic which these fabrication methods birthed, and use it to their advantage - in the same way concrete shaped the simplicity of modernism, we now have the liberty to create an entirely new alphabet of design parameters, based on our machines.

From a more philosophical stand, I think also the dystopian view of machines stealing our work is a great error. Whoever worked with machines knows that there is a loooooot of human inputting into the process, and that machines work for humans and not against them.

8. When will Mass Customization reach a truly global scale? What is missing to reach that point?

Eva: In my opinion, it is already happening, slowly… of course, it is connected with the level of the knowledge of the tools and the infrastructure providers. Sooner or later mass customization will be a part of our everyday life. 3D printing and other digital fabrication machining are enabling fast mass customization and increased variety of final products.

This will be more effective when those methods will be combined with traditional manufacturing. Of course, the architecture of products won't be as simple, but reduced cost of 3D printing and demand for variety and customization will drive architectural innovation to support more and more use of 3D printing. It may evolve that the parts which give products diversity could be printed at home what will be supported by online communities of designers who will share and sell the digital designs online.

Lidia: I think we need to teach designers, architects, engineers and other creatives or makers to embrace a parametric workflow. Starting from an early age. With a few exceptions, education is still traditional and the ones shaping the future have to go through a long process of “breaking” the system which they were brought up in, instead of starting from a point where they already are familiar with a algorithmical process.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

That’s it for this seventh episode of Designers Corner! Would you like to be featured in this space? Make sure to contact us! Just send an email to contact@shapediver.com and tell us about your work!

![Designers Corner [Ep. 7] – Eva Blšáková & Lidia Ratoi](https://assets.shapediver.com/img_sb_mig/1600x0/filters:format(webp)/f/92524/1423x870/309c12e868/6.webp)